International Relations, Principal Theories

Anne-Marie Slaughter

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1

B. Realism ............................................................................................................................................. 2

C. Institutionalism ................................................................................................................................. 8

D. Liberalism ....................................................................................................................................... 14

E. Constructivism ................................................................................................................................ 19

F. The English School ......................................................................................................................... 24

G. Critical Approaches ........................................................................................................................ 26

H. Conclusion ...................................................................................................................................... 28

A. Introduction

The study of international relations takes a wide range of theoretical approaches. Some emerge from within the discipline itself; others have been imported, in whole or in part, from disciplines such as economics or sociology. Indeed, few social scientific theories have not been applied to the study of relations amongst nations. Many theories of international relations are internally and externally contested, and few scholars believe only in one or another. In spite of this diversity, several major schools of thought are discernable, differentiated principally by the variables they emphasize—eg military power, material interests, or ideological beliefs.

B. Realism

For Realists (sometimes termed ‘structural Realists’ or ‘Neorealists’, as opposed to the earlier ‘classical Realists’) the international system is defined by anarchy—the absence of a central authority (Waltz). States are sovereign and thus autonomous of each other; no inherent structure or society can emerge or even exist to order relations between them. They are bound only by forcible → coercion or their own → consent.

In such an anarchic system, State power is the key—indeed, the only—variable of interest, because only through power can States defend themselves and hope to survive. Realism can understand power in a variety of ways—eg militarily, economically, diplomatically—but ultimately emphasizes the distribution of coercive material capacity as the determinant of international politics.

This vision of the world rests on four assumptions (Mearsheimer 1994). First, Realists claim that survival is the principal goal of every State. Foreign invasion and occupation are thus the most pressing threats that any State faces. Even if domestic interests, strategic culture, or commitment to a set of national ideals would dictate more benevolent or co-operative international goals, the anarchy of the international system requires that States constantly ensure that they have sufficient power to defend themselves and advance their material interests necessary for survival. Second, Realists hold States to be rational actors. This means that, given the goal of survival, States will act as best they can in order to maximize their likelihood of continuing to exist. Third, Realists assume that all States possess some military capacity, and no State knows what its neighbors intend precisely. The world, in other words, is dangerous and uncertain. Fourth, in such a world it is the Great Powers—the States with most economic clout and, especially, military might, that are decisive. In this view international relations is essentially a story of Great Power politics.

Realists also diverge on some issues. So-called offensive Realists maintain that, in order to ensure survival, States will seek to maximize their power relative to others (Mearsheimer 2001). If rival countries possess enough power to threaten a State, it can never be safe. → Hegemony is thus the best strategy for a country to pursue, if it can. Defensive Realists, in contrast, believe that domination is an unwise strategy for State survival (Waltz 1979). They note that seeking hegemony may bring a State into dangerous conflicts with its peers. Instead, defensive Realists emphasize the stability of → balance of power systems, where a roughly equal distribution of power amongst States ensures that none will risk attacking another. ‘Polarity’—the distribution of power amongst the Great Powers—is thus a key concept in Realist theory.

Realists’ overriding emphasis on anarchy and power leads them to a dim view of international law and international institutions (Mearsheimer 1994). Indeed, Realists believe such facets of international politics to be merely epiphenomenal; that is, they reflect the balance of power, but do not constrain or influence State behaviour. In an anarchic system with no hierarchical authority, Realists argue that law can only be enforced through State power. But why would any State choose to expend its precious power on enforcement unless it had a direct material interest in the outcome? And if enforcement is impossible and cheating likely, why would any State agree to co-operate through a treaty or institution in the first place?

Thus States may create international law and international institutions, and may enforce the rules they codify. However, it is not the rules themselves that determine why a State acts a particular way, but instead the underlying material interests and power relations. International law is thus a symptom of State behaviour, not a cause.

C. Institutionalism

Institutionalists share many of Realism’s assumptions about the international system—that it is anarchic, that States are self-interested, rational actors seeking to survive while increasing their material conditions, and that uncertainty pervades relations between countries. However, Institutionalism relies on microeconomic theory and game theory to reach a radically different conclusion—that co-operation between nations is possible.

The central insight is that co-operation may be a rational, self-interested strategy for countries to pursue under certain conditions (Keohane 1984). Consider two trading partners. If both countries lower their tariffs they will trade more and each will become more prosperous, but neither wants to lower barriers unless it can be sure the other will too. Realists doubt such co-operation can be sustained in the absence of coercive power because both countries would have incentives to say they are opening to trade, dump their goods onto the other country’s markets, and not allow any imports.

Institutionalists, in contrast, argue that institutions—defined as a set of rules, norms, practices and decision-making procedures that shape expectations—can overcome the uncertainty that undermines co-operation. First, institutions extend the time horizon of interactions, creating an iterated game rather than a single round. Countries agreeing on ad hoc tariffs may indeed benefit from tricking their neighbors in any one round of negotiations. But countries that know they must interact with the same partners repeatedly through an institution will instead have incentives to comply with agreements in the short term so that they might continue to extract the benefits of co-operation in the long term.

Institutions thus enhance the utility of a good reputation to countries; they also make punishment more credible.

Second, Institutionalists argue that institutions increase information about State behaviour. Recall that uncertainty is a significant reason Realists doubt co-operation can be sustained. Institutions collect information about State behaviour and often make judgments of compliance or non-compliance with particular rules. States thus know they will not be able to ‘get away with it’ if they do not comply with a given rule.

Third, Institutionalists note that institutions can greatly increase efficiency. It is costly for States to negotiate with one another on an ad hoc basis. Institutions can reduce the transaction costs of co-ordination by providing a centralized forum in which States can meet. They also provide ‘focal points’—established rules and norms—that allow a wide array of States to quickly settle on a certain course of action. Institutionalism thus provides an explanation for international co-operation based on the same theoretical assumptions that lead Realists to be skeptical of international law and institutions.

One way for international lawyers to understand Institutionalism is as a rationalist theoretical and empirical account of how and why international law works. Many of the conclusions reached by Institutionalist scholars will not be surprising to international lawyers, most of whom have long understood the role that → reciprocity and reputation play in bolstering international legal obligations. At its best, however, Institutionalist insights, backed up by careful empirical studies of international institutions broadly defined, can help international lawyers and policymakers in designing more effective and durable institutions and regimes.

D. Liberalism

Liberalism makes for a more complex and less cohesive body of theory than Realism or Institutionalism. The basic insight of the theory is that the national characteristics of individual States matter for their international relations. This view contrasts sharply with both Realist and Institutionalist accounts, in which all States have essentially the same goals and behaviours (at least internationally)—self-interested actors pursuing wealth or survival. Liberal theorists have often emphasized the unique behaviour of liberal States, though more recent work has sought to extend the theory to a general domestic characteristics-based explanation of international relations.

One of the most prominent developments within liberal theory has been the phenomenon known as the democratic peace (Doyle). First imagined by Immanuel Kant, the democratic peace describes the absence of war between liberal States, defined as mature liberal democracies. Scholars have subjected this claim to extensive statistical analysis and found, with perhaps the exception of a few borderline cases, it to hold (Brown Lynn-Jones and Miller). Less clear, however, is the theory behind this empirical fact. Theorists of international relations have yet to create a compelling theory of why democratic States do not fight each other. Moreover, the road to the democratic peace may be a particularly bloody one; Edward Mansfield and Jack Snyder have demonstrated convincingly that democratizing States are more likely to go to war than either autocracies or liberal democracies.

Andrew Moravcsik has developed a more general liberal theory of international relations, based on three core assumptions: (i) individuals and private groups, not States, are the fundamental actors in world politics (→ Non-State Actors); (ii) States represent some dominant subset of domestic society, whose interests they serve; and (iii) the configuration of these preferences across the international system determines State behaviour (Moravcsik). Concerns about the distribution of power or the role of information are taken as fixed constraints on the interplay of socially-derived State preferences.

In this view States are not simply ‘black boxes’ seeking to survive and prosper in an anarchic system. They are configurations of individual and group interests who then project those interests into the international system through a particular kind of government. Survival may very well remain a key goal. But commercial interests or ideological beliefs may also be important.

Liberal theories are often challenging for international lawyers, because international law has few mechanisms for taking the nature of domestic preferences or regime-type into account. These theories are most useful as sources of insight in designing international institutions, such as courts, that are intended to have an impact on domestic politics or to link up to domestic institutions. The complementary-based jurisdiction of the → International Criminal Court (ICC) is a case in point; understanding the commission of war crimes or crimes against humanity in terms of the domestic structure of a government—typically an absence of any checks and balances—can help lawyers understand why complementary jurisdiction may have a greater impact on the strength of a domestic judicial system over the long term than primary jurisdiction (→ International Criminal Courts and Tribunals, Complementarity and Jurisdiction).

E. Constructivism

Constructivism is not a theory, but rather an ontology: A set of assumptions about the world and human motivation and agency. Its counterpart is not Realism, Institutionalism, or Liberalism, but rather Rationalism. By challenging the rationalist framework that undergirds many theories of international relations, Constructivists create constructivist alternatives in each of these families of theories.

In the Constructivist account, the variables of interest to scholars—eg military power, trade relations, international institutions, or domestic preferences—are not important because they are objective facts about the world, but rather because they have certain social meanings (Wendt 2000). This meaning is constructed from a complex and specific mix of history, ideas, norms, and beliefs which scholars must understand if they are to explain State behaviour. For example, Constructivists argue that the nuclear arsenals of the United Kingdom and China, though comparably destructive, have very different meanings to the United States that translate into very different patterns of interaction (Wendt 1995). To take another example, Iain Johnston argues that China has traditionally acted according to Realist assumptions in international relations, but based not on the objective structure of the international system but rather on a specific historical strategic culture.

A focus on the social context in which international relations occur leads Constructivists to emphasize issues of identity and belief (for this reason Constructivist theories are sometimes called ideational). The perception of friends and enemies, in-groups and out-groups, fairness and justice all become key determinant of a State’s behaviour. While some Constructivists would accept that States are self-interested, rational actors, they would stress that varying identities and beliefs belie the simplistic notions of rationality under which States pursue simply survival, power, or wealth.

Constructivism is also attentive to the role of social norms in international politics. Following March and Olsen, Constructivists distinguish between a ‘logic of consequences’—where actions are rationally chosen to maximize the interests of a State—and ‘logic of appropriateness’, where rationality is heavily mediated by social norms. For example, Constructivists would argue that the norm of State sovereignty has profoundly influenced international relations, creating a predisposition for non-interference that precedes any cost-benefit analysis States may undertake. These arguments fit under the Institutionalist rubric of explaining international co-operation, but based on constructed attitudes rather than the rational pursuit of objective interests.

Perhaps because of their interest in beliefs and ideology, Constructivism has also emphasized the role of non-State actors more than other approaches. For example, scholars have noted the role of transnational actors like NGOs or transnational corporations in altering State beliefs about issues like the use of land mines in war or international trade. Such ‘norm entrepreneurs’ are able to influence State behaviour through rhetoric or other forms of lobbying, persuasion, and shaming (Keck and Sikkink). Constructivists have also noted the role of international institutions as actors in their own right. While Institutionalist theories, for example, see institutions largely as the passive tools of States, Constructivism notes that international bureaucracies may seek to pursue their own interests (eg free trade or → human rights protection) even against the wishes of the States that created them (Barnett and Finnemore).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

I Kant Zum ewigen Frieden (Friedrich Nicolovius Königsberg 1795, reprinted by Reclam Ditzingen 1998).

H Bull The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics (Macmillan London 1977).

KN Waltz Theory of International Politics (Addison-Wesley Reading 1979).

RO Keohane After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton University Press Princeton 1984).

RD Putnam ‘Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games’ (1988) 42 IntlOrg 427–60.

JG March and JP Olsen Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics (The Free Press New York 1989).

DA Baldwin (ed) Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate (Columbia University Press New York 1993).

JJ Mearsheimer ‘The False Promise of International Institutions’ (1994) 19(3) International Security 5–49.

JD Fearon ‘Rationalist Explanations for War’ (1995) 49 IntlOrg 379–414.

AI Johnston Cultural Realism: Strategic Culture and Grand Strategy in Chinese History (Princeton University Press Princeton 1995).

A Wendt ‘Constructing International Politics’ (1995) 20(1) International Security 71–81.

ME Brown SM Lynn-Jones and SE Miller (eds) Debating the Democratic Peace (MIT Cambridge 1996).

RW Cox and TJ Sinclair Approaches to World Order (CUP Cambridge 1996).

MW Doyle Ways of War and Peace: Realism, Liberalism, and Socialism (Norton New York 1997).

HV Milner Interests, Institutions, and Information: Domestic Politics and International Relations (Princeton University Press Princeton 1997).

A Moravcsik ‘Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics’ (1997) 51 IntlOrg 513–53.

ME Keck and K Sikkink Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics (Cornell University Press Ithaca 1998).

R Powell In the Shadow of Power: States and Strategies in International Politics (Princeton University Press Princeton 1999).

KOW Abbott and others ‘The Concept of Legalization’ (2000) 54 IntlOrg 401–19.

A Wendt Social Theory of International Politics (CUP Cambridge 2000).

B Koremenos (ed) ‘The Rational Design of International Institutions’ (2001) 55 IntlOrg 761–1103.

JJ Mearsheimer The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (Norton New York 2001).

MN Barnett and M Finnemore Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics (Cornell University Press Ithaca 2004).

ED Mansfield and J Snyder Electing to Fight: Why Emerging Democracies Go to War (MIT Cambridge 2005).

BA Ackerly M Stern and J True (eds) Feminist Methodologies for International Relations (CUP Cambridge 2006).

Published in: Wolfrum, R. (Ed.) Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law (Oxford University Press, 2011) www.mpepil.com

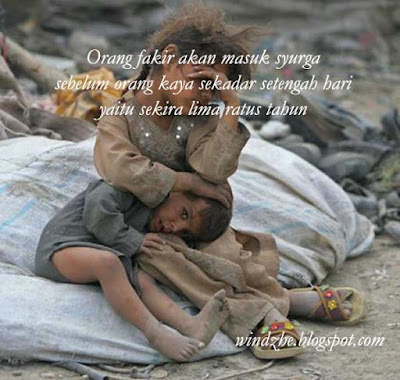

Sejenak Pagi:

Sejenak Pagi: